Operational Deficiencies at Benazir Income Support Programme Cash Points: A Critical Analysis

Operational Deficiencies at Benazir Income Support Programme

Executive Summary

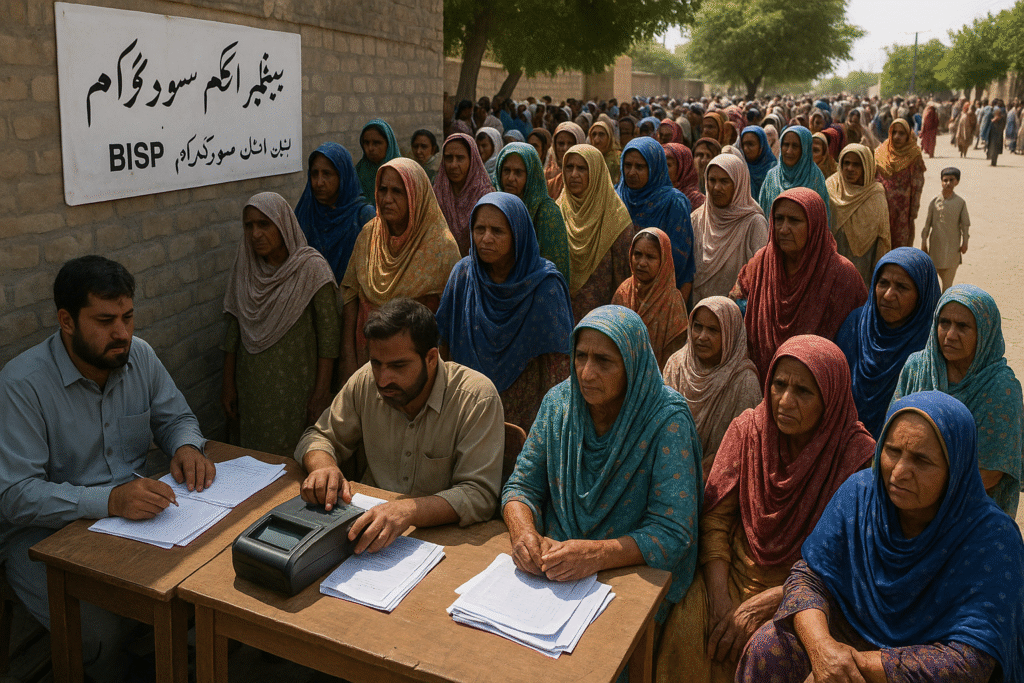

The Benazir Income Support Programme (BISP) stands as Pakistan’s most extensive social safety net, crucial for poverty reduction and the empowerment of vulnerable women. Its recent strategic pivot from campsite-based to a retail-based cash disbursement model was intended to enhance dignity, accessibility, and security for its millions of beneficiaries. However, this report critically examines the operational realities on the ground, revealing significant challenges that undermine these laudable objectives.

Despite the shift, BISP cash points frequently suffer from a severe lack of basic physical facilities, including adequate waiting areas, shade, drinking water, and washrooms. This deficiency, coupled with persistent overcrowding due to an insufficient number of operational outlets, subjects vulnerable beneficiaries—predominantly women, the elderly, and disabled individuals—to considerable hardship and indignity, particularly in harsh weather conditions.

A more alarming issue is the widespread exploitation of beneficiaries through illegal deductions, often facilitated by a “retail mafia” and potentially enabled by monopolistic practices within the partner bank networks. These unauthorized charges significantly erode the financial assistance intended for the poorest families, diminishing the program’s impact on poverty alleviation and fostering a profound erosion of trust in the system. Furthermore, logistical and technical hurdles, such as unfixed timings, cash unavailability, and biometric verification failures, exacerbate beneficiary suffering by necessitating multiple, often futile, trips.

While BISP has initiated measures, including issuing directives to banks, establishing helplines, and taking action against fraudulent retailers, these efforts appear largely reactive and have yet to address the systemic roots of the problems effectively. The proposed long-term solution of direct bank transfers, while promising, also presents a paradox: it could inadvertently exclude beneficiaries lacking digital literacy or access to formal banking infrastructure. This report concludes by emphasizing the urgent need for comprehensive, proactive reforms that prioritize beneficiary welfare, strengthen oversight, and ensure the program’s integrity and effectiveness in delivering dignified financial support.

Introduction: The Benazir Income Support Programme (BISP) and its Evolving Disbursement Landscape

The Benazir Income Support Programme (BISP), established in July 2008, serves as Pakistan’s flagship federal unconditional cash transfer initiative, designed to alleviate poverty and enhance social protection.1 Its inception was a direct response to severe economic challenges, including escalating food, fuel, and financial crises, aiming to cushion their adverse impact on the nation’s most vulnerable populations.2 Beyond immediate consumption smoothing, BISP’s long-term objectives include providing a minimum income support package to the poorest and most susceptible households, fostering financial inclusion, and strengthening the overall social safety net.1 A defining characteristic of the program is its explicit focus on empowering women, with cash transfers predominantly directed to female heads of households. This strategy is believed to ensure funds are spent effectively within the household and to enhance women’s decision-making power, contributing to broader gender equality.1

Beneficiary identification is meticulously managed through the National Socio-Economic Registry (NSER), which employs a Proxy Means Test (PMT) to objectively target the poorest 25% of the population, ensuring that support reaches those genuinely in need.1 The program’s substantial financial commitment underscores its national importance, with its budget significantly increased to Rs 716-720 billion for the upcoming fiscal year, reflecting a strong governmental resolve towards social protection.8

Historically, BISP relied on campsite-based disbursement methods, which frequently resulted in large gatherings and prolonged waits in challenging outdoor conditions.4 In a pivotal operational shift, BISP finalized preparations in June 2025 to distribute its fourth-quarter payments through a newly adopted retail network model.4 This strategic transition was primarily motivated by the imperative to protect beneficiaries from extreme weather conditions, particularly the ongoing nationwide heatwave, and to replace the less dignified and often crowded outdoor payment campsites.4 The stated objectives of this new model were to enhance accessibility, improve convenience, and ensure a more dignified, transparent, and secure cash transfer experience for millions of beneficiaries.4 Key features were intended to include efficient biometric verification processes and the provision of printed receipts to bolster transparency and accountability.11

This detailed article aims to provide a critical examination of the operational challenges and specific facilities lacking at these newly adopted BISP retail cash points. It will delve into the profound impact of these deficiencies on the vulnerable beneficiary population, analyze the underlying systemic issues contributing to these problems, and propose actionable recommendations for enhancing service delivery and ensuring the program’s intended benefits are fully realized.

Operational Challenges and Lacking Facilities at BISP Cash Points

The transition to a retail-based disbursement model, while conceptually sound, has been plagued by a series of operational challenges and critical deficiencies at the ground level. These issues significantly impede the program’s effectiveness and its ability to deliver dignified support.

Inadequate Physical Infrastructure

A pervasive and deeply concerning issue at BISP retail cash points is the severe deficiency in basic physical amenities. Despite the shift to a retail model being partly motivated by the need to protect beneficiaries from harsh weather conditions 4, numerous reports indicate a glaring absence of fundamental facilities. In Attock, for instance, a designated retailer shop was found to be operating in a building entirely devoid of a waiting room, washroom, or access to drinking water.13 This critical lack of infrastructure forces beneficiaries, many of whom are vulnerable women, to endure prolonged waits “under direct sunlight for hours” 13, directly contradicting the program’s stated aim of providing a safer and more dignified environment.11

While BISP leadership has explicitly directed partner banks to ensure the provision of “seating, shade, and drinking water” at retail outlets 12, the on-ground reality, as evidenced in areas like Attock, reveals a substantial gap between policy directives and their actual implementation. The persistence of these problems, despite official directives, points to a significant disconnect between BISP’s policy intentions and the actual implementation by its partner banks and their retail networks. This suggests a systemic failure in either the monitoring mechanisms, the enforcement of contractual obligations with banks, or the accountability framework for non-compliance. If basic welfare provisions mandated by BISP are not being met, it raises serious questions about the program’s overall operational control and its ability to ensure that its partners uphold service quality standards. This situation ultimately undermines the program’s credibility and its capacity to deliver on its promise of dignified assistance, potentially leading to a loss of trust among beneficiaries and the wider public.

Overcrowding and Accessibility Barriers

Despite the retail model’s explicit objective to “reduce crowding and long waits” 4, severe overcrowding remains a pervasive issue at many disbursement points. This is primarily attributable to an insufficient number of operational cash points relative to the vast beneficiary population. In Shangla, for example, a single disbursement point serving an entire tehsil leads to “severe problems to women” and consistently “overcrowded” conditions.15 This observation is corroborated by broader findings, with a World Bank-related report noting that “the current setup of one DRC per Tehsil leads to capacity issues, resulting in overcrowding and long wait times”.7 Such bottlenecks compel beneficiaries, who frequently travel with children and male relatives, to endure “long queues” for extended periods.15

The geographical concentration of these limited points imposes substantial financial burdens, with beneficiaries from “far off villages” sometimes expending “half of the whole BISP stipend on fare” just to reach the disbursement site.15 This directly counteracts the program’s core objective of providing meaningful financial relief. Furthermore, the disparity in retailer availability is stark; in Attock, only 2 retailers were operational for over 10,000 beneficiaries, whereas the stipulated criteria required 26, highlighting a severe and widespread shortage of authorized disbursement agents.13 The problem is not merely the

type of disbursement point, but the insufficient density and uneven distribution of these points. The retail network has not been scaled adequately to meet the demand of millions of beneficiaries, effectively replicating the very crowding issues it sought to alleviate. This also points to a lack of geographic equity in service provision, disproportionately impacting rural and remote beneficiaries. This operational oversight suggests a failure in comprehensive planning for scalability and equitable access. It means that despite the policy shift, the fundamental barrier of physical access and time burden remains, leading to continued hardship and potentially excluding some of the most vulnerable beneficiaries who cannot afford the time or cost of travel to distant, crowded points.

Systemic Vulnerabilities and Beneficiary Exploitation

The transition to the retail model has unfortunately been marred by widespread reports of systemic exploitation. Beneficiaries consistently complain of “unauthorized ‘commission’ charged by unscrupulous elements” or a pervasive “retail mafia”.16 These illegal deductions significantly diminish the actual financial assistance received, with amounts ranging from Rs 300 15 to Rs 1,500 17 and even exceeding Rs 2,000-3,000.18 Evidence of such malpractices is concrete, with retailers caught “red-handed” deducting money.17 Beyond financial exploitation, beneficiaries also report instances of bribery, harassment, and being coerced into “separate rooms” 18, highlighting a severe breach of trust and dignity.

A critical structural vulnerability is the alleged “monopoly” granted to certain franchisers by partner banks, as observed in Sahiwal. Here, a single franchiser (Farooq Mobiles) was given exclusive distribution rights, enabling “substantial financial exploitation”.19 This suggests a potential nexus between bank favoritism and exploitative practices, undermining fair competition and beneficiary protection. BISP has acknowledged “increasing incidents of fraud and mismanagement” 20 and has taken reactive measures, including blacklisting 12 retailers in Sahiwal 19 and arresting 49 individuals in Sargodha.17 However, the continued prevalence of such complaints, despite these actions, indicates that the problem is deeply entrenched. Directives to prohibit “unauthorized auto-withdrawals” 12 further underscore the ongoing nature of these exploitative practices. The “retail mafia” is not merely an isolated criminal activity; it represents a systemic leakage point that fundamentally undermines the integrity and effectiveness of the BISP program. The deductions directly reduce the effective value of the cash transfers, meaning the program’s intended poverty reduction impact is significantly diluted. This transforms a social safety net into a source of further financial burden for the poor. Beyond financial loss, the exploitation, harassment, and feeling of being “treated like animals” 15 lead to a profound erosion of trust in the program and government institutions. This can disincentivize beneficiaries from even attempting to collect payments, or from reporting abuses, creating a cycle of silent suffering. This crisis of trust and financial erosion necessitates not just reactive arrests but fundamental structural reforms in partner selection, oversight, and anti-corruption mechanisms to restore the program’s legitimacy and ensure its benefits reach the intended recipients fully and with dignity.

Logistical and Technical Hurdles

Beyond physical deficiencies and exploitation, beneficiaries are frequently confronted with significant logistical and technical impediments at cash points. A common complaint is the absence of “fixed timings” for retailers, compelling beneficiaries to wait for prolonged and unpredictable durations.13 This lack of predictability exacerbates the hardship, particularly for those traveling from afar. Furthermore, issues such as inconsistent “cash availability at retail outlets” 4 and persistent challenges with “biometric verification processes” 4 are frequently reported. While consistent internet connectivity is a mandated requirement for retail outlets 11, its unreliability often contributes to transaction failures and delays. The cumulative effect of these operational inefficiencies is that some beneficiaries are forced to visit centers for “several days” without successfully receiving their payments 18, incurring additional travel costs and lost daily wages, thereby further diminishing the real value of their stipend. These operational flaws lead to multiple trips, extended waiting times, and often, failure to receive payments on the first attempt. While not direct theft, these inefficiencies impose significant

opportunity costs (lost wages, time spent waiting) and direct costs (repeated travel fares) on beneficiaries. These hidden costs effectively reduce the net financial benefit of the cash transfer, making it less impactful for poverty alleviation. This highlights that even without overt fraud, poor operational management can significantly impede access and erode the value of social protection programs. It points to a need for more rigorous performance standards for partner banks, including real-time monitoring of operational metrics (like transaction success rates, wait times, and cash availability) to ensure that the system is not just technically present but functionally effective and truly convenient for beneficiaries.

Communication and Information Gaps

Effective communication is crucial for any large-scale social program, yet BISP faces significant challenges in this area. While BISP field staff are explicitly instructed to “intensify communication efforts so beneficiaries are well-informed about the new payment process ahead of the rollout” 11, the persistence of issues suggests these efforts are insufficient or ineffective. The widespread prevalence of fraudulent “prize schemes” and fake mobile messages, against which BISP has had to issue warnings 16, indicates a critical vulnerability to misinformation among beneficiaries. This suggests a lack of clear, consistent, and trusted official communication channels. Furthermore, BISP found it necessary to introduce “strict safety guidelines” and focus on “educating women about safe withdrawal practices, avoiding middlemen and maintaining privacy of personal data”.20 This underscores that beneficiaries often lack the essential knowledge and awareness required to navigate the disbursement process safely and protect themselves from exploitation. An information vacuum created by inadequate official communication and education allows unscrupulous actors to thrive. Beneficiaries, particularly those with lower literacy or limited access to official channels, become highly susceptible to misinformation, false promises, and exploitative practices because they are unaware of their rights, the correct procedures, or the exact amount they are entitled to. This information asymmetry is a critical enabler of exploitation. Even if physical facilities improve and more cash points are established, without empowering beneficiaries through clear, consistent, and accessible information, they will remain vulnerable. Effective communication is not just an administrative task; it is a vital component of beneficiary protection and program integrity, transforming passive recipients into informed participants capable of asserting their rights and identifying fraud.

The following table summarizes the key operational challenges and their direct consequences:

Table 1: Key Lacking Facilities and Their Consequences at BISP Cash Points

| Category of Lacking/Issue | Specific Lacking/Issue | Direct Consequences for Beneficiaries | Relevant Snippet IDs |

| Physical Infrastructure | No waiting room, washroom, drinking water | Exposure to harsh weather, physical discomfort, health risks, indignity | 12 |

| Accessibility & Capacity | Insufficient number of retailers/points | Overcrowding, long queues, high travel costs, significant time burden, reduced access | 7 |

| Exploitation & Security | Illegal deductions/commission by retailers | Financial loss, harassment, erosion of trust, diminished program impact | 15 |

| Operational Inefficiency | Unfixed timings, cash unavailability | Multiple trips, delayed payments, wasted time, additional travel costs, frustration | 4 |

| Information Gaps | Vulnerability to fraud/misinformation, lack of awareness | Mismanagement of funds, continued exploitation, reduced ability to report issues, distrust in system | 11 |

Profound Impact on Vulnerable Beneficiaries

The operational deficiencies at BISP cash points translate directly into severe hardships for the program’s beneficiaries, fundamentally undermining the very purpose of the social safety net.

Hardship and Indignity

The lack of fundamental facilities such as shade, seating, and clean drinking water, compounded by excessively long waiting periods in harsh weather conditions, subjects BISP beneficiaries—a demographic largely comprising vulnerable women, the elderly, and individuals with disabilities—to severe physical discomfort and potential health risks.13 This directly contravenes the program’s stated aim of providing assistance with “dignity and respect”.11 The reported experiences of being treated “like animals” 15 and facing harassment 18 at disbursement points strip beneficiaries of their inherent dignity and self-worth. This is particularly poignant given that the program specifically targets women for empowerment 1, and such demeaning treatment undermines this core objective. The physical and emotional toll is exacerbated for women who often travel long distances from remote areas, frequently accompanied by young children, making the arduous journey and wait an immense burden.4

Financial Erosion

The pervasive issue of illegal deductions by retailers, which can range from hundreds to thousands of rupees per transaction 15, directly and significantly reduces the actual amount of financial assistance received by the poorest families. This unauthorized “tax” on the vulnerable effectively dilutes the intended impact of the cash transfers on consumption smoothing and poverty alleviation. These are not merely inconveniences; they represent a

de facto reduction in the cash transfer’s value. The program’s effectiveness should be measured by the net benefit received by beneficiaries, not just the gross amount disbursed. The costs imposed by the system (exploitation, inefficiency) directly subtract from the intended poverty alleviation impact.

Furthermore, the high travel costs incurred by beneficiaries to reach distant, often singular, disbursement points further diminish the net benefit of the stipend. Some beneficiaries report spending “half of the whole BISP stipend on fare” 15, rendering the assistance marginally impactful. The necessity of making multiple trips due to operational inefficiencies like unfixed timings or cash unavailability 13 adds to these travel expenses and results in lost daily wages for beneficiaries, who are often daily wage earners or cannot afford to miss work. This hidden erosion of funds means that the substantial budgetary allocation for BISP 8 yields a lower real return on investment in terms of poverty reduction. It creates a situation where the system designed to uplift the poor inadvertently extracts value from them, exacerbating their financial vulnerability rather than alleviating it. This situation necessitates a re-evaluation of the true cost-effectiveness of the current disbursement model.

Erosion of Trust

The cumulative experiences of exploitation, harassment, and consistently poor service delivery at BISP cash points inevitably lead to deep disappointment, anger, and a profound erosion of trust among beneficiaries.15 When a program designed to provide vital support becomes a source of further hardship and indignity, it fundamentally breaks the implicit social contract between the state and its most vulnerable citizens. The widespread prevalence of fraud and misinformation campaigns, including fake messages and prize schemes 16, further undermines beneficiaries’ confidence in the program’s integrity and official communications. This atmosphere of distrust can lead to reduced participation, a reluctance to report legitimate issues due to fear of reprisal or futility, and a general sense of disempowerment among the target population. Such erosion of trust ultimately hinders the program’s long-term sustainability, its ability to adapt and improve, and its overall effectiveness as a tool for social cohesion. When a state-led social safety net, intended to be a beacon of support, becomes a source of further hardship and exploitation, it directly undermines the program’s legitimacy in the eyes of its beneficiaries. The promise of “dignity and respect” 11 is not merely an operational guideline but a cornerstone of trust. This erosion of trust extends beyond BISP itself; it can foster broader disillusionment with government initiatives and institutions. It jeopardizes public support for social protection programs and can make it more challenging to implement future reforms or expand their reach. A program that loses the trust of its target population risks becoming ineffective, regardless of its budget or noble intentions, as beneficiaries may disengage or become more vulnerable to exploitation.

Current Measures and Government Initiatives to Address Challenges

BISP has acknowledged the operational challenges and the exploitation faced by its beneficiaries and has initiated various measures to address these issues.

Review of BISP’s Directives to Partner Banks for Facility Improvements

BISP leadership has actively engaged with its strategic banking partners to address ongoing disbursement challenges. High-level meetings, such as those chaired by BISP Additional Secretary Dr. Tahir Noor with banks like HBL, have focused on improving on-ground service delivery.4 Specific directives have been issued to partner banks, compelling them to ensure the provision of “essential facilities such as drinking water, shaded waiting areas, and seating arrangements” at all retail outlets.12 Banks are also instructed to guarantee that these outlets are “fully operational, with trained staff, biometric verification systems, consistent internet connectivity, and clear signage” to assist recipients.11 These directives indicate an official recognition of the existing deficiencies and an intent to rectify them.

Assessment of Established Complaint Mechanisms, Helplines, and Control Rooms

To provide recourse for beneficiaries, BISP has established a national helpline (0800-26477) for reporting issues.11 Beneficiaries are also advised to report any problems or complaints at their local BISP Tehsil offices.11 Furthermore, dedicated control rooms have been set up in various districts, such as Multan (contactable at 061-6511555), specifically to handle beneficiary complaints during disbursement hours and ensure their “timely and transparent resolution”.14 BISP and its partner banks have formally agreed to “devise a mechanism and establish a control system to address all complaints in a timely and effective manner” 12, signaling a commitment to grievance redressal.

Overview of Actions Taken Against Fraudulent Retailers and Efforts to Prevent Exploitation

In response to widespread complaints of illegal deductions, authorities have initiated targeted drives, leading to arrests (e.g., 49 individuals in Sargodha) and the recovery of illegally deducted funds.17 Assistant Commissioners have been actively involved in catching corrupt retailers “red-handed”.17 BISP inspection teams from central and regional offices have taken concrete steps, including blacklisting fraudulent retailers (e.g., 12 in Sahiwal) and submitting their data for permanent blacklisting under the Payment Complaint Management System.19 A “zero tolerance” approach has been reaffirmed against those exploiting the poor.17 Proactive measures also include BISP issuing “strict safety guidelines” and instructions aimed at educating women beneficiaries about safe withdrawal practices, the importance of avoiding middlemen, and safeguarding personal data, alongside warning against fraudulent “prize schemes” and fake mobile messages, advising trust only in messages from the official 8171 number.16

Despite these efforts, the core problems—lack of facilities, overcrowding, and rampant exploitation—continue to be widely reported and persist.13 This persistence suggests that the current measures, while necessary, are largely reactive (responding to complaints, punishing offenders) rather than proactive systemic reforms. They address the symptoms but may not be effectively tackling the root causes that enable these issues to recur, such as fundamental flaws in the partner oversight framework, insufficient network capacity, or inherent vulnerabilities in the disbursement model. The effectiveness of BISP’s directives and complaint mechanisms is limited if they are not backed by robust, continuous enforcement and accountability for partner banks. A shift in strategy is needed from a “whack-a-mole” approach (dealing with individual incidents) to a more comprehensive, preventative framework that targets the structural weaknesses enabling the “retail mafia” and ensures consistent adherence to service quality standards across the entire network.

Exploration of Proposed Long-Term Solutions

Recognizing the deep-seated issues with the current retail model, BISP Chairperson Senator Rubina Khalid has announced active efforts to transition to a more secure “banking system” where financial assistance will be directly deposited into each beneficiary’s bank account.16 This strategic move is explicitly aimed at “getting rid of this ‘retailer mafia'” and eliminating the role of “middlemen” who exploit beneficiaries.16 In parallel, BISP is also in negotiations with Pakistan Post to explore the possibility of disbursing financial assistance through its extensive network of post offices, offering another potential channel for secure and accessible payments.16 These initiatives reflect a commitment to fundamentally reform the disbursement mechanism to enhance transparency, dignity, and efficiency.

While direct bank transfers offer a powerful solution to the “retail mafia,” they introduce a new set of challenges related to digital and financial inclusion. Research indicates that mobile money (a proxy for digital financial literacy and access) is not widely used by the general population in Pakistan, particularly among vulnerable groups. Only 9% of surveyed adults use mobile money, and users are predominantly men (77%), urban (41%), and relatively more educated/financially included.21 Additionally, lack of relevant documentation like CNICs is a barrier to registration for BISP itself 7, which would also be a barrier to opening bank accounts. Many BISP beneficiaries, especially vulnerable women in remote rural areas, may lack existing bank accounts, the necessary documentation, digital literacy, or convenient access to banking infrastructure. An abrupt or unsupported transition could inadvertently create a new form of exclusion or shift exploitation to new avenues (e.g., charges for account opening, scams targeting digital illiteracy). This highlights a crucial paradox: a solution to one problem (exploitation by middlemen) could inadvertently create or exacerbate another (digital exclusion and new forms of vulnerability) if not managed carefully. The success of a direct bank transfer model hinges on comprehensive, parallel initiatives to promote financial literacy, facilitate easy and free bank account opening for all beneficiaries (especially women), and ensure widespread, accessible banking infrastructure, particularly in underserved rural areas. It demands a phased, supportive transition rather than a sudden shift, emphasizing that technological solutions must be accompanied by social and educational support.

The following table provides a comparative overview of BISP’s disbursement models, highlighting the gap between strategic intent and observed realities:

Table 2: BISP Disbursement Models: Intended Improvements vs. Persistent Challenges

| Disbursement Model | Key Features/Rationale | Intended Benefits (Retail Model) | Observed Challenges (Retail Model) | Relevant Snippet IDs |

| Traditional Campsite | Centralized, outdoor, often crowded | N/A | Overcrowding, long waits, exposure to harsh weather | 4 |

| Retail Model: Intended | Leveraging existing networks, biometric verification, dignity, transparency | Reduced crowding, safer environment, improved accessibility, transparency, dignified service, printed receipts | N/A | 4 |

| Retail Model: Observed | Decentralized through retail outlets | N/A | Lack of basic amenities (waiting room, washroom, water), persistent overcrowding, illegal deductions, technical issues (biometric, cash), unfixed timings, harassment | 12 |

Recommendations for Enhancing Service Delivery and Beneficiary Experience

To ensure BISP effectively fulfills its mandate and provides dignified, transparent, and impactful financial assistance, a multi-pronged approach focusing on systemic reforms and beneficiary-centric solutions is essential.

Strengthening Physical Infrastructure

It is imperative that BISP, in collaboration with partner banks, mandates the provision of essential amenities at all retail cash points. This includes ensuring readily available shaded waiting areas, adequate seating arrangements, access to clean drinking water, and functional, hygienic washrooms.12 These are not optional conveniences but fundamental necessities for dignified service, especially given Pakistan’s extreme weather conditions. A stringent system of regular, unannounced inspections by joint BISP and district administration teams must be implemented to ensure compliance. Partner banks and individual retailers found in violation of these mandatory facility standards must face immediate and significant penalties, including financial fines and, for repeated offenses, suspension or termination of their disbursement contracts.

Expanding and Diversifying the Retail Network

To effectively address persistent overcrowding and long waiting times, BISP must significantly increase the number of authorized retail outlets. This expansion should be strategically planned, prioritizing densely populated urban areas and, crucially, underserved remote villages where single points per tehsil currently cause immense hardship and travel burdens.7 Beyond traditional retail shops, BISP should actively explore and pilot diverse disbursement channels. This includes leveraging the extensive network of Pakistan Post offices, as already proposed 16, and carefully assessing the potential for expanding mobile money agent networks. However, any expansion into digital channels must be preceded by robust efforts to address the existing digital literacy and accessibility gaps among beneficiaries.21 The distribution of cash points must be equitable across all administrative units, moving away from monopolistic arrangements that limit access and foster exploitation.7 This involves a data-driven approach to identify underserved areas and allocate resources accordingly.

Implementing Robust Oversight and Anti-Corruption Measures

BISP needs to invest in and effectively utilize advanced real-time monitoring tools to track transactions, detect anomalies, and identify potential instances of illegal deductions or unusual activity.4 This should be complemented by increased frequency and rigor of on-ground monitoring and mystery shopper programs by BISP’s inspection teams. It is crucial to actively dismantle and prevent monopolistic practices among franchisers and retailers, which have been shown to enable widespread exploitation.19 BISP and partner banks must ensure a competitive environment for disbursement services, with clear guidelines for franchise allocation that prioritize beneficiary welfare over commercial interests. Investigations into alleged favoritism by banks in awarding franchises must be conducted transparently and lead to accountability. The existing grievance redressal systems (helplines, control rooms, Tehsil offices) must be made more effective and user-friendly.11 This includes ensuring prompt action on complaints, protecting the anonymity and safety of complainants, and providing timely feedback on the resolution status. Community-level focal persons could also be designated to assist beneficiaries in filing complaints. The drives against corrupt retailers and staff involved in illegal deductions and harassment must continue and intensify. Swift legal action, coupled with permanent blacklisting from the BISP network and public dissemination of such actions, is crucial to deter future malpractices.17

Improving Technical Reliability and Cash Liquidity

Partner banks must be held strictly accountable for ensuring continuous and sufficient cash availability at all authorized retail outlets throughout the disbursement period. This is critical to prevent beneficiaries from making multiple, futile trips and enduring unnecessary waits.4 Investment in upgrading and maintaining more robust and reliable biometric verification systems is necessary to minimize transaction failures. Crucially, alternative, secure verification methods must be readily available and efficiently processed for beneficiaries who consistently face issues with biometric authentication.4 Furthermore, consistent internet connectivity at all disbursement points must be ensured to facilitate smooth transactions. BISP must enforce and monitor fixed, predictable operating hours for all retailers, eliminating the uncertainty and prolonged waits caused by unfixed timings.11

Enhancing Beneficiary Education and Grievance Redressal

Extensive, multi-channel communication campaigns utilizing local languages, community radio, public service announcements, and direct outreach by BISP field staff are essential. These campaigns should clearly educate beneficiaries about the exact amount of their entitlement, the correct disbursement process, their rights, and, crucially, how to identify and report illegal deductions or harassment.11 The official BISP helpline (8171) must be prominently publicized as the sole trusted source of information. The process for filing complaints must be made exceptionally simple and accessible. This could involve having dedicated BISP representatives present at high-volume disbursement points to assist beneficiaries, or developing a simplified SMS-based reporting system that is easy to use for all. As BISP progresses towards direct bank transfers, a massive, sustained investment in financial literacy programs for beneficiaries is paramount. These programs, tailored to the specific needs of vulnerable women and rural populations, should educate them on the basics of bank accounts, digital transactions, ATM usage, and cybersecurity best practices.16

Fostering Digital Financial Inclusion

The proposed shift to direct bank transfers 16 should be implemented gradually, starting with pilot programs in selected areas. This phased approach allows for identification and resolution of challenges before a full-scale rollout. Crucially, it must be accompanied by comprehensive support mechanisms to ensure that no beneficiary is inadvertently excluded due to a lack of bank accounts, digital literacy, or access to banking infrastructure. Active collaboration with partner banks is needed to facilitate easy, free, and accessible bank account opening for all eligible beneficiaries, particularly women. This could involve mobile bank account opening camps at community levels or even at existing disbursement points, simplifying the process and removing barriers like documentation requirements.7 While current mobile money usage among BISP’s target demographic is low 21, the high mobile phone ownership presents a significant opportunity. Targeted educational initiatives and incentives could be designed to increase familiarity and utilization of mobile money, potentially integrating it as a complementary disbursement channel once digital literacy and trust are sufficiently built.

Conclusion

In conclusion, while the Benazir Income Support Programme’s strategic shift to a retail-based cash disbursement model represented a commendable and necessary step towards enhancing beneficiary experience and upholding dignity, its implementation has been significantly undermined by a critical lack of basic facilities, persistent overcrowding, and rampant exploitation by unscrupulous middlemen. These operational deficiencies and systemic vulnerabilities are not mere inconveniences; they inflict immense physical hardship and emotional indignity upon Pakistan’s most vulnerable segments of society, particularly women, the elderly, and individuals with disabilities. Crucially, they directly erode the financial benefits intended by the program, thereby diminishing its core objectives of poverty reduction and fostering financial inclusion.

The analysis reveals a persistent gap between BISP’s policy intentions and the on-ground realities, highlighting a need for more robust oversight and accountability mechanisms for partner banks. While BISP has initiated reactive measures such as issuing directives, establishing helplines, and taking action against fraudulent retailers, the pervasive nature of the challenges underscores that these steps, though necessary, are insufficient to fundamentally alter the exploitative environment.

Therefore, it is imperative for BISP and its partner institutions to move beyond a reactive stance towards comprehensive, proactive reforms. This includes rigorously enforcing mandatory facility standards at all cash points, strategically expanding and diversifying the retail network to ensure equitable access, implementing stringent anti-corruption measures that dismantle monopolistic practices, and ensuring the technical reliability of disbursement systems. Furthermore, a supportive and phased approach to digital financial inclusion, coupled with extensive beneficiary education on their rights and safe practices, is critical. Only through such concerted, multi-pronged efforts can BISP truly fulfill its mandate of providing timely, transparent, and, most importantly, dignified financial assistance to Pakistan’s vulnerable populations, ensuring that the vital cash transfers genuinely translate into improved welfare, empowerment, and a restored sense of trust in the social safety net.

About khanahmad6720@gmail.com

Author at TopNow.news

khanahmad6720@gmail.com is a contributor to TopNow.news, focusing on local updates and government programs in Punjab. (Full bio coming soon).